Our Major Publications

Our Peer Accepted and Published Articles

Historical Review

The history of open surgical treatment of herniated lumbar discs started over sixty years ago. Williams described Microlumbar Discectomy in 1978. This is a small incision technique using an external overhead microscope. It is, of course, a small open operation which requires a posterior midline skin incision of at least one inch (for one level), incision of paravertebral fascia, detachment of muscle, removal of a portion of the ligamentum flavum, usually bone removal, retraction of the root and dural sac, and opening of the disc inside the spinal canal.

Minimally invasive endoscopic methods, performed by passing the scope from the skin surface, should be differentiated from open surgery. These are puncture opening (percutaneous) procedures, (with skin openings just large enough to admit the scope), for internal viewing through scope placement directly at the tissue, to be addressed as compared to working from an external view, (either with or without a microscope), through an open incision.

The evolution of these percutaneous methods to the current state-of-the-art can be traced with an historical overview of the basic approaches: chemonucleolysis, laser, manual, and automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy, and arthroscopy. In 1948, Valls, et al., and in 1956, Craig, described the posterior lateral approach for bone biopsy. Lyman Smith first used Chymopapain to treat a lumbar disc disorder in 1964. The posterolateral extradural route to the lumbar disc was described by Day in 1969. Percutaneous nucleotomy was developed by Hijikata in 1975; Kambin, in 1983, and thereafter, described arthroscopic techniques and equipment for posterior and posterolateral herniated disc removal, via intradiscal access. Then, in 1985, Onik developed the nucleotome for automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy. In 1987, Choy reported using laser to treat herniated lumbar discs. Subsequently, in 1993, percutaneous endoscopic discectomy with a medium-size, straight, rigid endoscope, at L4-5 and above, was described by Mayer and Brock, in a prospective, randomized series of cases, using manual and automated tools; they reported 95% of endoscopic patients returning to their previous occupations, compared to 72% in their open microdiscectomy group.

More recently, Kambin and others have described larger scope “foraminal access” approaches, but since straight scopes will not go around corners, and large scopes will not pass into small openings, these efforts have been limited to working inside the foramen, or perhaps reaching tools though the foramen, without the advantage of having the entire scope go through in such a way that the scope itself is directly on the actual herniation.

The small, guided endoscopic, completely transforaminal technique (the subject of this paper) was described in detail at the AANS meeting in April, 1996 [8], and was commended by Dr. Dunsker, an official of the AANS, as “the surgery of the future.”(pers. comm.)

Pictures

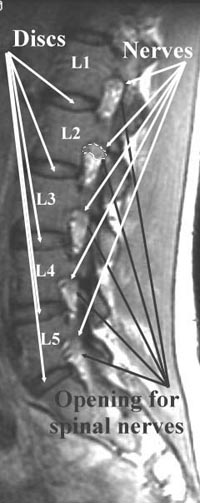

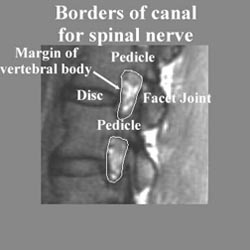

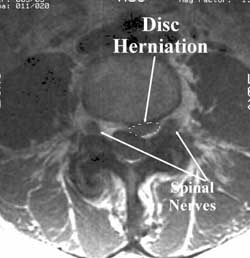

The spinal nerve on the left side of the picture is in the “neural foramen”–a canal or doorway for the nerve to leave the spinal canal and go out into the body.

Disc herniations, bone spurs from the vertebral body and bone spurs from the facet joints can press on the nerve in the neural foramen

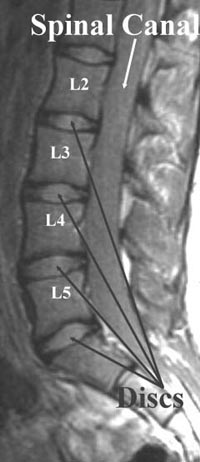

This shows what normal discs look like in the lower back. The central part has a significant amount of water within it and behaves something like jello or like an expensive gel-filled seat cushion.

This inner part of the disc, the nucleus, is a bright gray on these pictures. The outer part of the disc, the annulus, is a tough, fibrous layer that is strong.

It keeps the softer nucleus in place. It is dark on these pictures and looks the same as the edges of the bone. The inner part of the bone, the bone marrow, contains cells that produce red and white blood cells

The spinal nerves are in the upper part of the “neural foramina”, or openings or doorways for the spinal nerves, as they go from the spine to the rest of the body.

At L2 (the 2nd lumbar vertebra), the spinal nerve is circled with a white line. The bright material below the nerve is fatty tissue.

The L45 disc (short arrow) is not as bright as the discs near the top of the picture because it has partially dried out. Aging and injury cause a disc to lose water.

The loss of water weakens the disc and decreases its “shock absorber” capabilities. In this case, a fragment of the central part of the disc has slipped backwards and upwards, to narrow the spinal canal

The fine white line surrounds the “neural foramen” or doorway through which the spinal nerves leave the spinal canal to spread out into the body.

This neural foramen can be narrowed by disc herniations, spurs from the margin of the vertebral body, or spurs from the facet joints

In this patient, a fragment of the L4-5 disc has extruded outside its normal location and is pushing into the spinal canal.

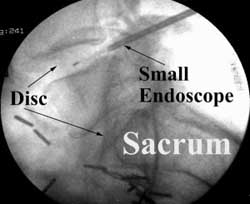

During minimally invasive surgery for disc herniation, a small endoscope with fiber optics is directed from the skin to the disc.

In the picture left, the endoscope is in the L45 disc.